Mildred Howard: A Survey, 1978 – 2020

Mildred Howard’s survey at Parrasch Heijnen Gallery in Los Angeles takes an important look at this artist whose career has spanned more than 40 years. Exhibiting since the late 70s, Howard’s first installations involved the use of windows and storefronts. Over the ensuing decades, her work has included sculptural assemblage, installation, 2D collage, and photographic processes. This show at Parrasch Heijnen presents a solid overview of her range of practices over the years.

Born in San Francisco in 1945, and currently living in Berkeley, Howard first took to dance but later found her way to visual art. She began her studies of art at the College of Alameda, graduating in 1977, and then with Textile Arts at John F. Kennedy University where she earned an MFA in 1985. Her work is known for engaging with themes of community, class struggle, racial injustice and memory.

Howard appears as an artist moving through material and ideas as if they were nourishment—harvesting objects, breaking down their substance, and absorbing their vital elements. There is a sense of freedom and dedication to the thought of her art that gives it a mood of freshness, engagement, and a life lived of experience. In the deeper currents of her work, where stories are told of violence endured by those oppressed and marginalized, the poetic and the critical come together. Her clarity with material as a narrative force allows her stories to be told as fluidly as if they were written on paper.

“Just because you don’t see something, it doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist…”

Mildred Howard, from ‘Mildred Howard’s houses hold memories’, video, SFMOMA

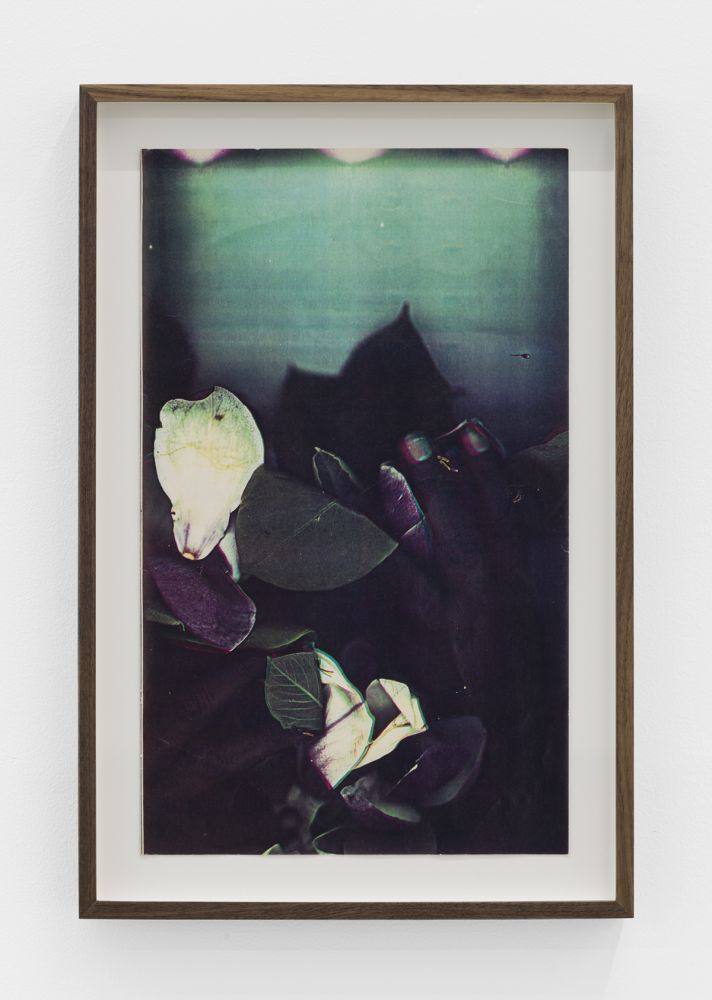

color Xerox photo collage

14 x 8-1/2 inches

(image courtesy Parrasch Heijnen Gallery)

Her color Xerox photo collages for example brilliantly capture the poetic effortlessness she composes an image with. These look to be made by placing objects on the flatbed glass of a Xerox copy machine and the results printed out. Two of these, Untitled (1979) and Untitled (1980), show flowers and foliage arranged on the glass. In one of them, you can see what appears to be the artist’s hand.

The backgrounds of the two Xerox collages have different hues, revealing even greater aesthetic depth. A sense of place-setting is offered here, reinforced by the copy machine’s looking-glass interiority. They read as somewhat funerary, and also as if the viewer was peering at the scenery through a window.

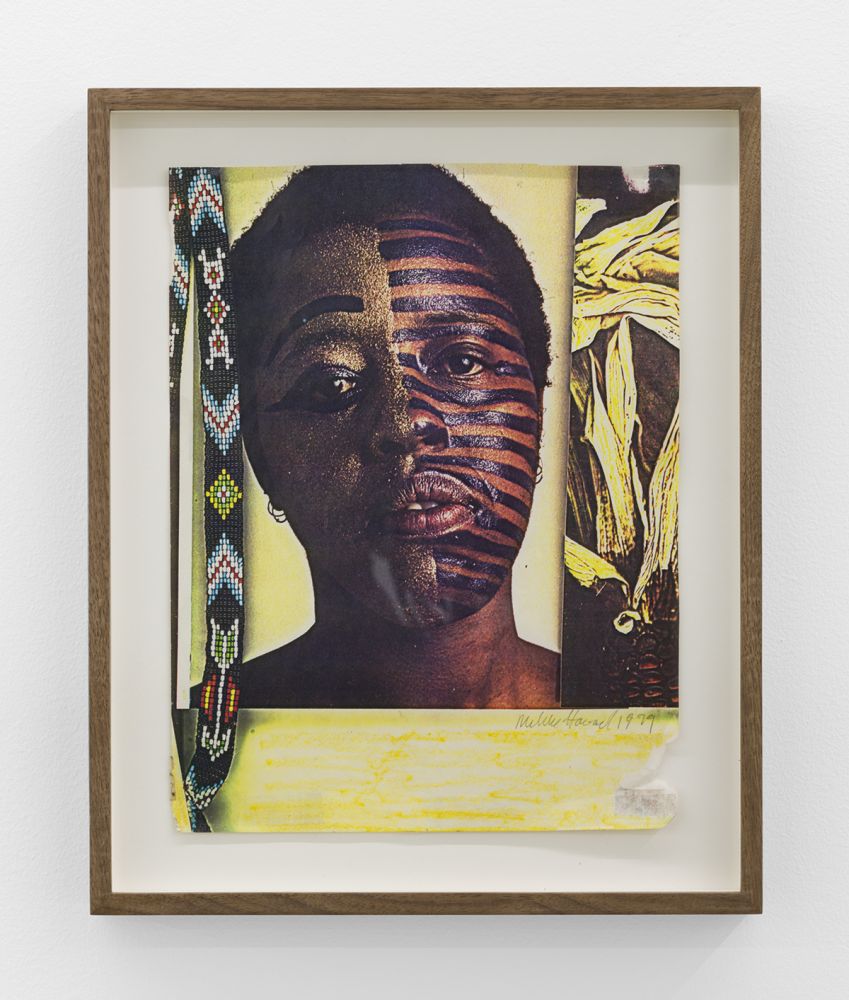

color Xerox photo collage

11-7/8 x 8-3/8 inches

(image courtesy Parrasch Heijnen Gallery)

In a third collage, Untitled (1979), a face appears—of the artist herself. Her face is shown half-painted on one side with stripes and the other in speckled gold. She is bordered by a hand-braided strap and a fabric print of grain on either side. If the flowers from the other works seem funereal, this one looks like a celebration of life, of becoming, of growth.

…But hopefully, there’s something in that work that will trigger that person to see the world in a whole different way, and as a result of that, it may help the viewer to search a little bit more about the meanings of things.

Mildred Howard, from ‘Mildred Howard’s houses hold memories’, Video, SFMOMA

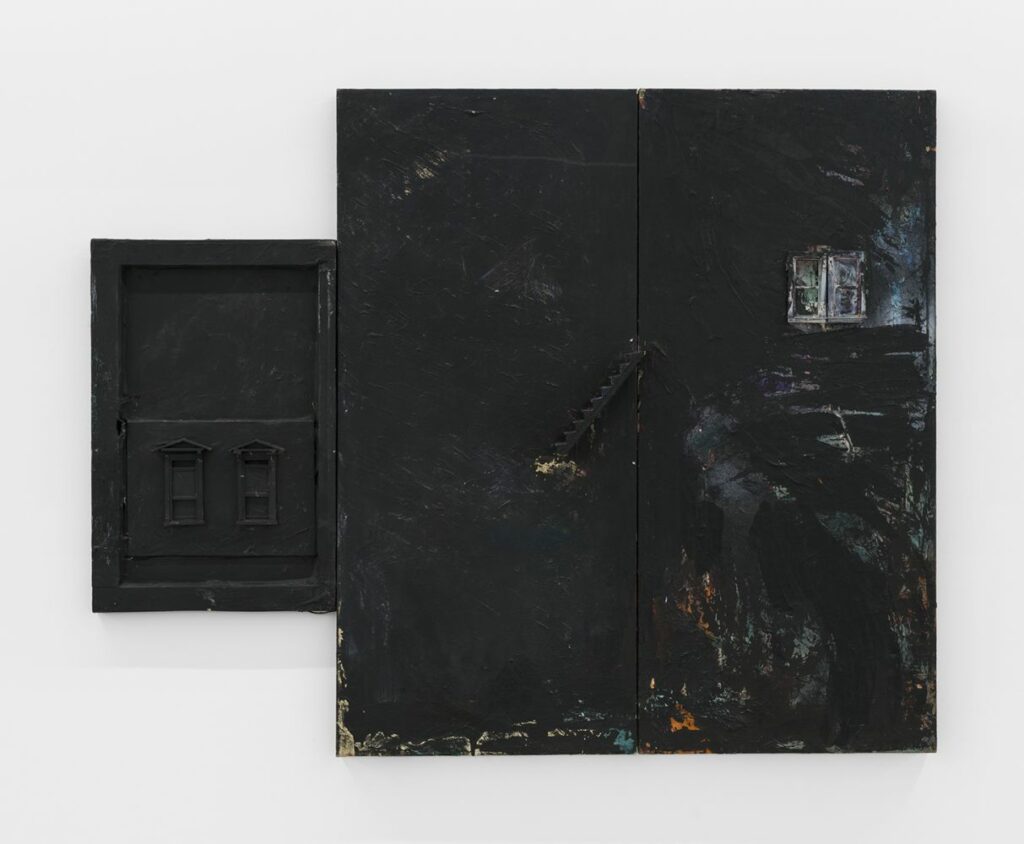

acrylic and mixed media

three-part painting with house elements

(image courtesy Parrasch Heijnen Gallery)

Howard’s life-giving touch to collage naturally carries over into sculptural assemblage. Two of her works in the show, from the 80s and 90s, take a more reflective turn toward personal and social events. In the work 3328 Royal Blue (1984) a composition with few elements is shown: a small staircase, a window, and an attached framed panel with another pair of windows—all in black. There are some faint traces of color, a little orange at the bottom, and a wash of blue swirling off on the right.

The elements in this work illustrate the facade of a house, flattened out and in fragments. The distance between components on the black field gives rise to considerations of both space and time and that a very real, personal memory is involved. Questions about this narrative offer the viewer a chance to dig deeper, enter into the picture themselves, and search for “the meanings of things”.

(detail)

(image courtesy Parrasch Heijnen Gallery)

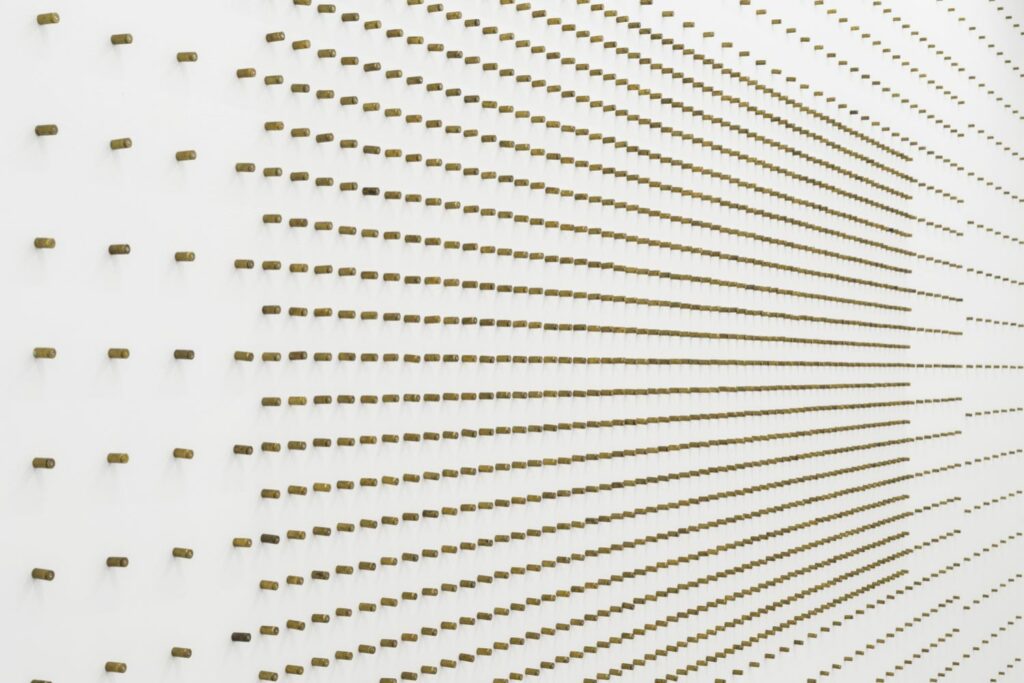

In the work Ten Little Children Standing in a line (One Got Shot, and Then There Were Nine) (1991), a very direct memory is referenced. The title of the work seems to say it all, yet the narrative created by the installation explains even more. On a pedestal, several hands made out of copper are placed upright. Installed on the wall behind it are hundreds of brass bullet casings protruding from the wall. On the wall to the side is an enlarged news clipping from 1976, showing the photo of a slain 13-year-old Hector Pieterson—a South African schoolboy who was shot and killed during the Soweto uprising in South Africa. Nearly 20,000 students stood and protested at Soweto. Pieterson was one of just hundreds killed there.

Mixed media installation (brass bullet casings, copper glove molds, photomural),

dimensions variable.

(Image courtesy Parrasch Heijnen Gallery)

In homage to the students, the arrangement of the copper glove molds appears like children with their hands raised in a classroom. The metal is one that can tarnish but can be polished to reveal a beautiful and rich color—a metaphor for both the vulnerability and preciousness of life.

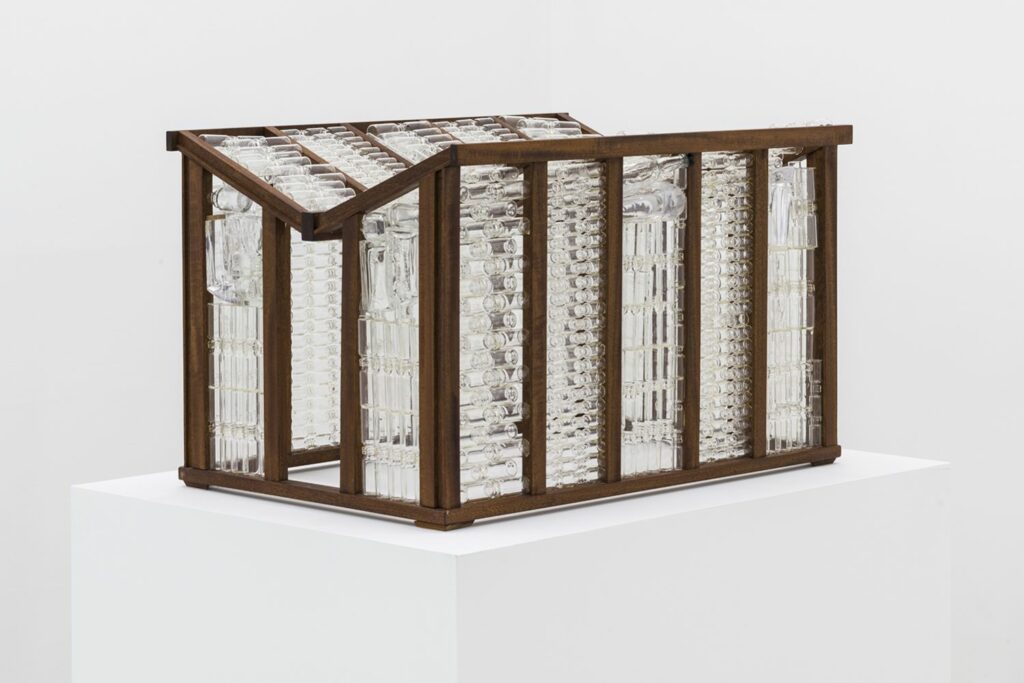

found glass bottles, wood, glue

17-1/2 x 28-1/2 x 18-7/8 inches

(image courtesy Parrasch Heijnen Gallery)

In examples of her most recent work, Howard has created sculptures of model houses. These are composed of wood frames with the walls filled with glass bottles she collected. According to the gallery’s press release, these are a combination of Joseph Eichler’s modernist architecture and a model of slave quarters. Eichler was a Californian architect and real estate developer in the mid-1900s who designed and sold homes with a strict non-discrimination policy. His designs were often open and airy, with ample light allowed in through windows and skylights. The glass bottles in Howard’s models suggest that those once treated as slaves have a home to enter and bathe themselves in the light of their interiors. The refractions of light from the bottles cause the entire dwelling space inside to glow.

In a work from 2007, Volume I & II: The History of the United States with a few Parts Missing, Howard engages with the stories of those forced from overseas. According to the artist, the work took form by chance. She had been drilling random holes into books when she came across the history book The United States Since 1865. When she opened it up, she discovered that the holes surrounded the poem The New Colossus by Emma Lazarus, where she calls: “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses”

modified books with holding cases

13-1/4 x 9-1/2 x 2-1/2 inches each

(image courtesy Parrasch Heijnen Gallery)

The work is poignant for our present moment, a time when walls threaten our borders, families seeking refuge are imprisoned, and many seeking status are deported. After the Immigration Act of 1924—as pointed out by the book in Howard’s work—the doors were closed to newcomers. Just a hundred years later, the country today finds itself swimming in familiar waters.

As the holes in Howard’s new book of history suggest, parts of the story are missing. There are narratives behind the surface pointing to things unseen. The stories are of individuals and communities with lifetimes of experience to be told. Their voices have not always been heard, and the injustices they’ve faced have not been put into books, but in memory, they remain in truth. As Howard reminds us, “just because you don’t see something doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.” Her advice tells us there are things we need to look for and listen to—to acknowledge these stories, memorialize them, and prove their value still promises victory over ignorance.