Mary Simpson: The Matriarch of Nature Revealed

Mary Simpson’s work bridges visual abstraction with ideas relating to the ancient world and its mysteries. In a work from 2010, for example, a video displays an image with two arms, one in color and one in grayscale, interacting with footage captured in black and white. The title of the work, Marsyas, is a reference to the ancient Hellenic god (also known as the satyr Pan) who challenged the solar god Apollo to a music contest and lost. The punishment for his hubris was to have his skin flayed while alive. He was then hung upside down from a tree to bleed out.

In Marsyas, the narrative alludes to a figure stripped of its body, displaced, and relegated to a sightless search for the feeling touch of an object captured as an image, accompanied and assisted by its own shadow. The enigma of language and image association plays an essential role in this work, and as shown in other bodies of work to follow, is still a force present in Simpson’s work today.

Marsyas, 2010

Color 16mm film, silent, 1 minute 15 seconds

Keeping in line with the ancients, Simpson has since turned her focus to the bronze-age origins of the Eleusinian mysteries, a pagan society that practiced initiations and sacred rituals involving the goddess of grain and agriculture, Demeter, and her daughter Kore (also known as Persephone). As she describes in her own words:

I’m interested in Demeter as a goddess who was not of Olympian/patriarchal beliefs (man submitting to supreme beings), but rather of an earthbound sustainable ethic and matriarchal system. I’m tracing the female and earth-centric roots of this myth including the pagan origins of the mother/daughter goddesses being celebrated for thousands of years at the temple of Eleusis.

Mary Simpson, from an email exchange

Western culture has often ignored this focus on the goddess and an intrinsic matriarchal role in society for many centuries. Since the emergence of anti-pagan religious authorities in the 3rd century CE, beginning with Constantine, Western civilization’s relationship with nature and reverence for its sacred signatures seems to have been all but severed. In the wake that followed, often rigid and violent patriarchal systems dominated, distanced in their connection with the earth, the waters, and the skies.

In the past, lives were more aligned with agriculture, the seasons, and the movement of the stars. Cultures lived with the patterns of nature as an organizing structure of reality. In Simpson’s chosen myth of Demeter and Kore, for example, Kore spends her life in the underworld during the dark periods of the year—as reflected by the autumn and winter months—and she returned to the surface when days became longer and life flourished in the spring and summer. Thomas Taylor, an English translator from the 18th & 19th century, suggested that Kore’s return from the underworld represented a liberation of the soul from the infertile realm of the underworld, while her return to the realm above marked a period of renewal. Demeter’s joy was expressed with an abundance of nature’s beauty after her arrival.

oil on canvas

90 x 50 inches

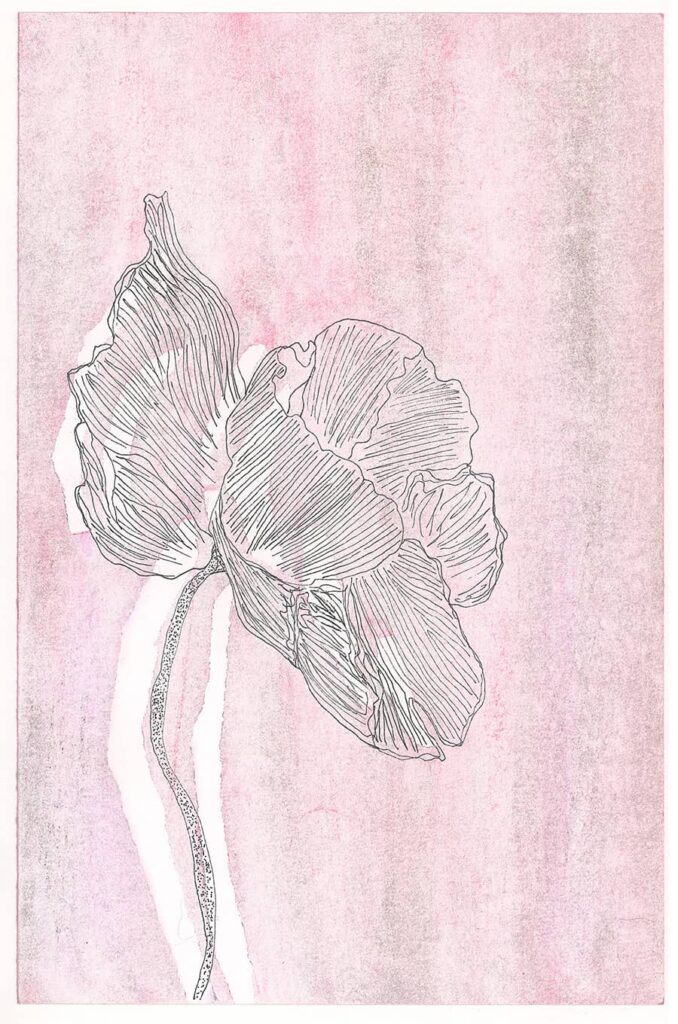

This relationship with nature appears avidly celebrated in Simpson’s work, where often a spare and honest sense of beauty joins with a longing reach for abstraction, and where poetic correspondences drawn up from a deep well become united with visual form. Like Kore’s journey to the underworld and back, Simpson’s work often displays a presence moving across the threshold of an abstract matrix. Like an actor placed before a backdrop of cosmic scenery, there is a figure, a shape or an object hovering between the space implied by the background of the image and the frame of her paintings. In some works, the subject is a primordial vessel implied by a grouping of lines, and in others, it is an abstract shape appearing like a hieroglyph. More recently, the form is an illustration of a flower.

acrylic, paper, oil and ink on maple

28 x 23 1/2 inches

Within this composition of elements (again thinking of the journey of Kore), there is a frequent narrative of dormancy and return. In a statement accompanying her 2015 exhibition Off Hours at Rachel Uffner in New York, Simpson describes this as a search for the image.

And so the image seeks a body—not an imprint, not transference—a body that can be seen in any light, beauty at low temperature. A device lights up one side of the face only, that which is turned towards it. A device is not older than we are. So we have to stay, pursuing an image, in the off hours.

Mary Simpson, from the press release to the exhibition ‘The Off Hours’

Oil on canvas

28 in x 30 in

This image, for Simpson, calls for a return to the primordial state before we slid into a world of disassociation, a world descriptive of where we are at now. In an underworld of our own perhaps, society exists separated from nature, lying dormant in the nether regions awaiting our return, our liberation. Sharing inspiration from a quote by the poet Hilda Doolittle, Simpson suggests our restoration occurs not through the built world of man, but through the form of the goddess of nature, Demeter.

Men, fires, feasts,

steps of temple, fore-stone, lintel,

step of white altar, fire and after-fire,

slaughter before,

fragment of burnt meat,

deep mystery, grapple of mind to reach

the tense thought,

power and wealth, purpose and prayer alike,

(men, fires, feasts, temple steps)—useless……never forget when you seek Pallas

H.D. (Hilda Doolittle), from the poem ‘Demeter’

and meet in thought

yourself drawn out from yourself

like the holy serpent,

never forget

in thought or mysterious trance—

I am greatest and least.

The greatest and least implies an enfolding of life contained within the embrace of Nature herself, while also suggesting a relationship to classical Hermetic thought—where the realm of the divine acts as bookends to the extremities of the cosmos, yet is also fully present in every single component of that universe. Doolittle reveals her hand as the author of a book of poetry titled Hermetic Definitions. A self-described “pagan mystic”, she grew up in a Pennsylvanian Moravian community with historic ties to a German mystic-pietist tradition, and we can trace this community back to earlier Hermetic-Rosicrucian communities. (John Amos Comenius, considered the founder of modern education, represents a historic figure in this lineage, as does the English mystic Jane Lead.)

In recent years, the subjects of liberation, nature, and the feminine have also framed Simpson’s exhibitions. For a show at Situations in 2018-19 titled Libido of the Forest, for example, she describes her inspiration derived out of current events.

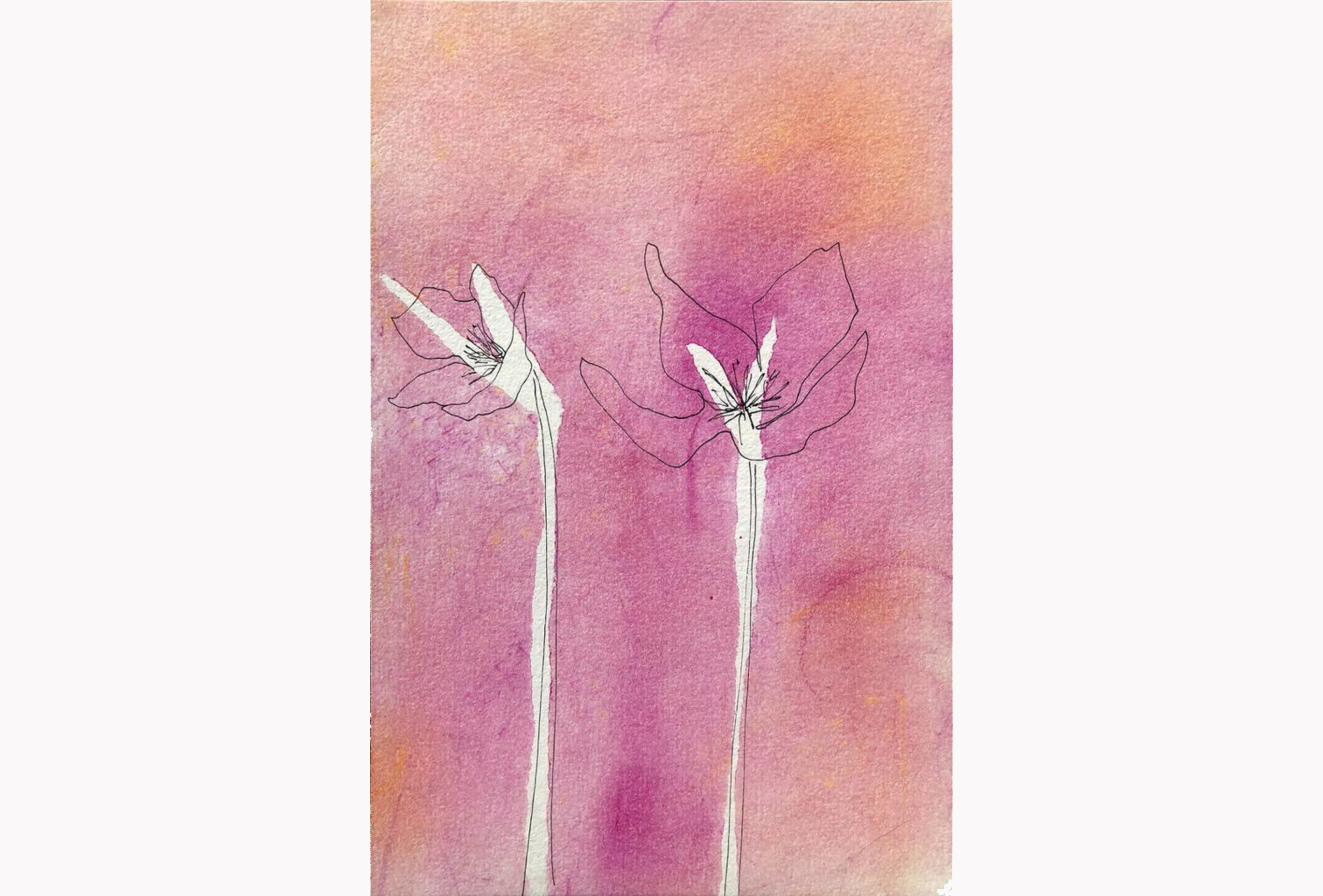

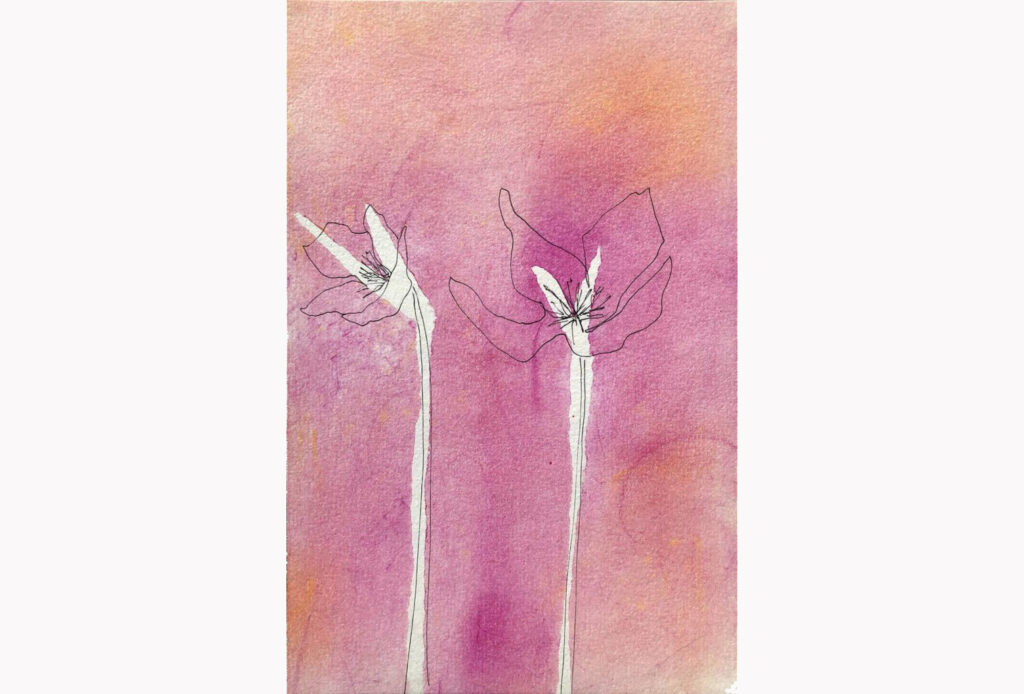

Shortly after traveling from New York to DC for the 2017 Women’s March, I felt an intense desire to inhabit an earthy, infinite range of feeling, to cultivate a curiosity of fragility, sadness, grief, rage and death but also a sensual fervor of joy—experiments in imagination. I felt compelled to draw flowers, every day. To paraphrase Beverly Dahlen in her 2008 essay “On Beauty,” beauty is not required for aesthetics (if it were, beauty would function merely as a commodity); beauty is essential for life.

Mary Simpson, from the press release to the exhibition ‘Libido of the Forest’

Pastel and ink on paper

8 1/2 x 5 1/2 inches

Simpson appears to be living out a narrative of nature and society acknowledging the divine Matriarch in real time.

In 2019, Simpson showed several of these illustrations in an exhibition titled Nature as Measure, curated by Candice Madey at Chambers Fine Art in Beijing. In these pastel and ink drawings, many of the same themes persist, with a pursuit of ideal beauty through representations of nature and their habitual creation combined. Quoting Beverly Dahlen again, she says:

As we would wish not to be orphaned in the world, nor abandoned, nor abused, so we would wish ‘wholeness, harmony, clarity,’ not only for ourselves, but for the world we live in… The question of beauty is an ethical question

Beverly Dahlen, from her 2008 essay ‘On Beauty’

To say that a daily practice of drawing flowers holds any element of activism might seem absurd. It is a very stupid thing to draw a rose. But balancing the brutal impacts of aggression with an unapologetic indulgence in beauty has, for me, felt completely necessary.

quoted by Mary Simpson in the press release for the exhibition ‘Libido of the Forest’

Pastel and ink on paper

8 1/2 x 5 1/2 inches

Although not that obvious, the ancient mysteries remain beneath the surface here in this work too. Considering Simpson’s analysis of beauty, her purposeful praxis, and her contemplation on the divine feminine, if we were to look back to someone like Plato (who was himself a pagan and initiated in the ancient mysteries) we find some parallels. In his Phaedrus, he put forth the idea that humanity experiences a higher purpose through an ascent of beauty, involved with nature on a cosmic scale. He also suggested in his Symposium that the human soul could ascend and become liberated through the higher form of celestial Aphrodite—the goddess of beauty and love. For many who studied under Plato (like his most famous student Aristotle) nature was the visible signature in the world that revealed this.

Recently, Simpson discovered a book by the author Nan Shepherd, titled The Living Mountain. It’s a book she describes as “unmatched by anyone” regarding a profound and vitalizing experience one can have with nature. Shepherd was a Scottish Mountaineer and lifelong explorer of the Cairngorm mountains who wrote impressions about her experiences with nature. In her writing are clues that appear to echo Simpson’s experience of art-making.

A certain kind of consciousness interacts with the mountain-forms to create this sense of beauty. Yet the forms must be there for the eye to see. And forms of a certain distinction: mere dollops won’t do it. It is, as with all creation, matter impregnated with mind: but the resultant issue is a living spirit, a glow in the consciousness, that perishes when the glow is dead. It is something snatched from non-being, that shadow which creeps in on us continuously and can be held off by continuous creative act. So, simply to look on anything, such as a mountain, with the love that penetrates to its essence, is to widen the domain of being in the vastness of non-being.

Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain

Pastel and ink on paper

8 1/2 x 5 1/2 inches

If the act of looking with a penetrating love widens our experience of the conjoined world—itself a disembodied experience of the greater reality of nature—and if the creative act holds back the shadow of the underworld, then it would seem that by making art with a profound reverence of nature that these two things might, at last, become realized (whilst never forgetting the greatest and the least). And if so, perhaps the act of drawing a rose becomes the most important thing in the world to do.

Mary Simpson was born in Anchorage, Alaska and currently lives in New York. She received an MFA from Columbia University and attended the Whitney Independent Study Program. Her work has shown at Bortolami Gallery, On Stellar Rays, Rachel Uffner Gallery and Simone Subal Gallery, all New York; David Petersen, Minneapolis; Almine Rech, Brussels; Hilary Crisp, London; Chambers Fine Art, Beijing; Seattle Art Museum; Boise Art Museum. Film Screenings, projects, and lectures include the Artists Institute, The Kitchen, Goethe Institute, all New York; Henry Art Gallery, Seattle; CAM2, Madrid.