Ryan Lauderdale: Haunted Futures

Ryan Lauderdale’s multi-disciplinary practice involves sculpture, photography, painting, and video. It often deals with the seductive qualities related to the materials he uses like light, reflective surfaces, and transparency. But to look at his work as a mere sum of its material effects, however, would fall short of the mark. It also addresses the ambient environment surrounding it. For the viewer, the locus of Lauderdale’s work is an expanded field where the work forms relationships with other things tangentially involved within its aesthetic nexus. Because of this, the influences he brings are also integral to his practice. Subjects like defunct shopping malls, brutalist architecture, ambient music—even theorist Mark Fisher’s discussion of Capitalist Realism— all shape the mood and tone of his sculptures, images, and paintings. The result is an approach to art-making where images, objects, and ideas belie an awareness of the residual aesthetic substance lingering in their peripheral arena.

Beginning with Lauderdale’s sculptural work, the materials he commonly uses are commercial and architectural in nature: Formica, metal, glass, and fluorescent light fixtures. Installed on the floor or on the wall, the sculptures transition between functionality and abstraction, while their use of light raises issues of domesticity as well as the light and space movement. Lauderdale often places discreet personal objects in his physical compositions too—for example, a rose, a glazed pot, or a small collectible. These items lend a personal, almost private, touch to the work.

Formica, birch plywood, fluorescent bulb, glass, mirrors, CB2 table parts, anodized aluminum, Ikea lamps, kelp noodles, resin, audio cords, zip-ties, power-strip, various hardware

The personal and private are further drawn out as Lauderdale places and documents his work within a domestic environment. The work Internal Pastoral stands as a perfect example here. Made out of the aforementioned Formica, fluorescent lights, and glass; the work also involves ready-made domestic components like CB2 table parts and Ikea lamps. These commercial products are combined with his own hand-made forms, producing a hybrid of the commercial and the personal. The transparent objects he makes from kelp noodles cast in resin, for example, are paired with incandescent lights; creating a warm, softened glow that disperses over the work. Audio cables, like the type used to plug in guitars to an amplifier, are used to connect different components in the work; customizing their intended use.

In reference to architecture, like many of Lauderdale’s works, Internal Pastoral is angular. Here, triangular parts rise into the air and defy gravity, like domestically-scaled architectural buttresses or scaffolds. The tiered-metal components and wiring add to the allusion to their industrial staging and purpose. Considering the contextual gravity of these works, however, which he calls “possible interiors”, several other issues emerge. First, is the suggestion of a more private, permanent space for the work to be shown in vs., say, the typical cold white walls of a gallery setting or the ubiquitous post feed. Today, it seems we generally consider artwork to have entered public discourse the moment it’s shared. But here, the object maintains a certain autonomy by its connection to the location it was documented in. It becomes somewhat liberated from the premature death caused by the scroll or the next show in the exhibition cycle. It has a place where it lives and belongs. The work also seems intent on revealing what our more inner, private relationships with objects and images might be.

This relationship, for acknowledging a role for consumer products, doesn’t, however, ignore the commercial reality we live in. Lauderdale’s sense of domesticity instead seems to ask for a commercial reality that cares. One that subverts the corporate, zombie-monopoly world we live in. One that seeks a path beyond the tallied numbers of likes and algorithms. Perhaps, one that might even offer a sense of personal, spiritual refuge within it. With Internal Pastoral, Lauderdale appears to be conjuring or lamenting the loss of these things. The work reaches for an alternate future through a re-activation of our present products; one that may even be fabricated from the aesthetic detritus of a dead-end and hopelessly optimistic past. This all toes the line with what the theorist Mark Fisher defined as “hauntology.”

“What Capitalist Realism blocks out is what Hauntology mourns for.”

—Mark Fisher. Lecture: ‘Capitalist Realism and Hauntology’, 2011

Fisher’s Capitalist Realism describes a state where only one reality is served: the individual’s participation in the classified strata of a socio-economic universe. According to Fisher, Capitalist Realism is a total state where everything—even culture and modern myth-making—is consumed by the forces of capitalism; abandoning all alternatives of tangible futures for models that only adhere to the prescribed standards of commercial circulation. In this environment, Hauntology arises to insist that there are futures beyond the limits of postmodernity’s terminal outcome. As Fisher says, “When the present has given up on the future, we must listen for the relics of the future in the unactivated potentials of the past.” Although Fisher’s view may sound bleak, it offers some optimism, in that within hauntology there is a “refusal to give up on the desire for the future…for a future that never arrived.” Hauntology, in other words, becomes a credo or an ideology upholding the right to an alternative future that is revealed through the creative auspices inherent to art.

Inkjet print, fluorescent bulb, formica, birch plywood, CB2 coffee table parts, anodized aluminum, hardware, latex

Thus, Lauderdale’s work—a work that “feels” itself within domestic and commercial realities we can’t deny— offers something of a remedy to postmodern malaise. His use of lights, glass, and other products creating moods for interior spaces nods to a different socio-economic future, one where we’re not all just users of products vying for influence, but where things are slowed down to waking-time and displayed in places where people gather to enjoy experiences with each other. With these associations, it’s no wonder that Lauderdale often refers to defunct shopping malls in his visual-aesthetic vocabulary. After all, the shopping mall presents to us another sense of hauntology, an allegory for a near-utopian reality where commerce and self-fulfillment once went hand-in-hand. Malls, for their time, can be thought of as architectural arenas where meaningful social events once took place. Where people could find each other while exploring their personal interests, such as in the record store, for example, or the arcade, the promenade, or even in the food court. In contrast, today our commercial realities are all private moments: we have Amazon, Netflix, and Instagram, used on screens we don’t share with others in person.

Appropriately, delivering a sense of calm, tranquility—a chill vibe—finds its way into the realm Lauderdale’s work occupies. In his own words, the works are “meditations on the aspirational promises offered” of things. In this sense, they can be thought of as barometers of aesthetic climates that generate their own atmosphere. The type of feeling here is what one might get from late-night off-air background music or smooth-jazz elevator music. The best parallel, though, is found in the musical genre of vaporwave, which holds many of the same aesthetic concerns. In vaporwave, commercial songs (typically from the 80s) are often slowed down and remixed to reveal surprisingly emotional and haunting sounds. Like Lauderdale’s work, vaporwave presents an emotional context for an alternate commercial reality, where the focus is to uncover the right atmosphere to make you feel relaxed, mystified, or blissed out. It’s the easter egg contained within the vestige of normalcy; the thing you didn’t realize was there which only becomes apparent when altering how it enters the senses.

printed laminate, plywood, fluorescent bulb, anodized aluminum, hardware, Elfa rack, wax, mirror

In pursuit of other architectures or in-situ environments to show his work in, Lauderdale has also installed his work outdoors. Placed out in what he calls the “cathedral of nature”, his work finds yet another atmospheric context to embrace. The work Gardenback, for example, was installed in the woods and left there indefinitely. After some time, he returned to photograph the work in the wintertime. With this, one is again led to consider the relationship between the private and public nature of art—as well as its meaning in the digital media age. If the familiar question poses, “Does a tree that falls in a forest make a sound if no one is there to hear it?” The question here becomes “Does an artwork installed in the forest exist if no one is there to see it in person?” The answer is an emphatic “yes”. And, given our relationship to art experienced through algorithmically-controlled post feeds, perhaps even more so. Lauderdale’s work is shown here tied to the earth— something perhaps more permanent than just another thing suggested for you to scroll past.

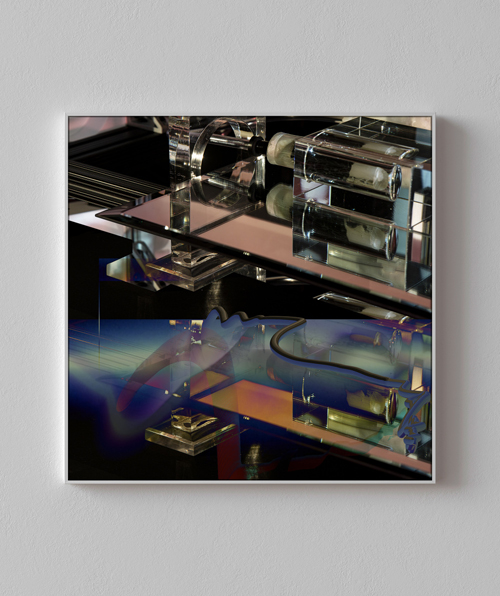

Dye Sublimation on Aluminum

30 x 30 inches

With Lauderdale’s 2D work, these concerns take another turn. A series of photographs, like Double Globe Felsen and Double Angel, involve images taken from his sculptures and then digitally collaged. In them, there are glimpses of surfaces, lights, cables, and hardware—caught in reflections and composed into layered images transferred to aluminum by dye-sublimation.

Dye Sublimation on Aluminum

30 x 30

The photographs present an interface between the physical and digital worlds, proving that Lauderdale isn’t just dealing with analog nostalgia, but with how the material translates into the immaterial, and how our perceptions of these things change through the ‘remixing’ of them. Here, the sculptural composition becomes abstracted and transformed into images that are further distorted through filters or transparencies. The physical, so to speak, is being pulled out of “normal” reality and dissolved into a kind of aesthetic aether.

acrylic on canvas

36×36 inches

Lauderdale’s paintings accomplish no less a performance with acrylic on canvas. He describes these as being originally designed as “backgrounds” for his sculptural works, but they nonetheless hold their own as standalone works. This concern with backgrounds would even seem to continue his exploration of the works’ aesthetic atmosphere. It’s easy to picture each work as a discreet figure establishing a relationship with others in this arena. As for the works themselves, titled Figure 1, Figure 2, or Figure 3…, they appear to be stenciled, almost like reproductions. Closer inspection, however, reveals unique paintings with lush, varying color schemes and differently-overlapping shapes. The shapes look like letters from some unknown language. The paintings overall come off like a series of unique editions—somehow both subverting and embracing the romantic ideal of painting at the same time.

acrylic on canvas

28×28

Because of their square format, the paintings also seem to reference product designs, such as album covers. With this idea, there is also the sense that the image on the surface is meant to be emblematic of its “interior content”. The idea is that there is something else behind the image, perhaps even a unique brand of communicative abstraction.

Ultimately, Lauderdale’s images and sculptures deal with sensible aesthetics, but they also address the challenges placed on art’s autonomy and production in the digital age. On one hand, we can’t escape the treadmill we’re on with regard to the media’s role and the economic universe we live in. But on the other, one wonders if anyone else notices that the treadmill doesn’t lead anywhere if the art in question doesn’t deliver or bring us somewhere else—and by this, whether or not we’re just going through the motions. By looking at the “aspirational promises” offered through various aesthetic languages, Lauderdale’s work suggests there is another purpose and place for art—one we perhaps don’t spend enough time considering. His work reminds us that there is an inner world occupied by art and that perhaps by discovering it, we might uncover its value.

All images ©Ryan Lauderdale