Alejandro Almanza Pereda: Physics of Freedom and Necessity

Mexican artist Alejandro Almanza Pereda has lived and worked at home and abroad over the past 18 years. Between the mid-2000s and mid-2010s, he spent several years in NYC. During this time, he began creating large installations involving a multitude of found objects that were stacked, balanced, and often appearing on the verge of collapse. Over the last 10 years, he started filming and photographing objects underwater.

In all of Almanza Pereda’s work, there is an attraction to the object that soon turns to awareness of its impact as a system within its physical environment. The scene usually portrays a counterbalance of trepidation, beauty, stress, and joy. Yet it’s Almanza Pereda’s intuition towards physical and aesthetic matters that keeps the viewer lingering.

Wardrobe, fluorescent light bulbs, fish tanks, water, decorative bricks, plant, bed sheets

Image courtesy of the artist

Almanza Pereda’s installations often incorporate unexpected objects like fluorescent tube lights, bowling balls, plants, and furniture. Although the works are static, they possess a fluid, kinetic energy. The lights, for example, might be used to hold up heavy things like platforms, pieces of concrete—as well as the aforementioned bowling balls. Plants might adorn the tops of fluorescent tube structures. Pieces of furniture might be on their side and holding something else up.

Fluorescent light bulbs, plants, glass, metal clamps

Image courtesy of the artist

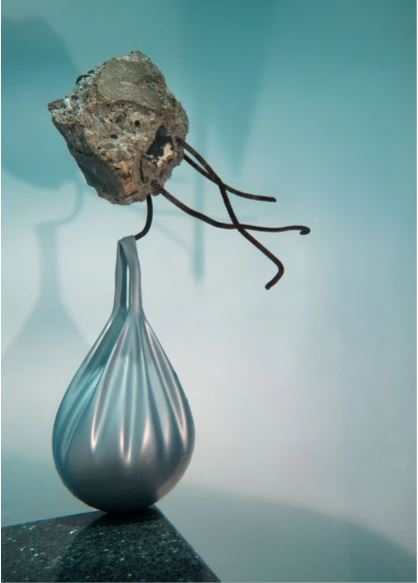

In his work there is also often a sense of material freedom—a shrugging off the rules or norms— however, it is combined with a sense of sublime visual aesthetics that hold everything together. The work sticks and stones n. 4, for example, shows a clear sense of how the objects’ ad-hoc physical integration leads to an understanding of its essential organization on an aesthetic level.

In the work, a classical-looking bust sitting on a stained-wood table is connected to a dark blue bowling ball via a cool white tube light. The dark blue bowling ball is then connected to an off-white concrete form on the ground with a golden rod. The off-white concrete form on the ground is connected to a light gray organic form stand through a silver rod. A rock atop the light gray form connects to an upright piece of black driftwood with another silver rod. The upright piece of black driftwood is standing atop what looks to be a billiard cueball, propped up by what looks to be a pool stick.

Driftwood, concrete, brass, steel, aluminum, wooden stool, fluorescent light bulb, found objects

Image courtesy of the artist

Physically, the objects appear to possess no hierarchy -perhaps even randomly selected- or maybe they’re just being used to hold another thing up. One imagines Almanza Pereda going out and collecting things and then later trying to figure out how to put these unlikely things together. But then, aesthetically, one gets a deeper impression. The work feels both modern and ancient; or utilitarian and romantic at the same time. The qualities, tones, hues, and textures of the objects work together in an unexpected way.

There is the profound sense that what Almanza Pereda has ended up with has been exquisitely fated or that some magic gravity has pulled everything together. This comes through as a resolve of the works’ unbridled physical nature, combined with its visual refinement. Although the work feels like a time capsule waiting to fall apart the moment you leave, the arrangement presents an organizational and aesthetic sense of belonging, despite how incongruent the individual components might first appear.

Spectrally, the work embraces both space and image; but this isn’t a 2D image — it’s a 3D image of aesthetic physics that one experiences in the round. Involving this sensibility, it probably comes as no surprise that when turning to photography and film, Almanza Pereda’s treatment of the 2D frame does something similar. His 2D work involves the poetic dynamics of spatial physics realized through the aesthetic image.

Speaking to Almanza Pereda, he describes the transition from sculpture to his underwater works starting as a process of exploration. He soon discovered “a new set of physical laws” to work with. In these works; objects, vegetables, or fruit are arranged on platforms or floating in underwater scenes. Things are connected together by string, gravity, or buoyancy— being either suspended or kept from floating away.

Underwater photograph

Image courtesy of the artist

In rock pepper, for example, a bundle of peppers is tied with string and connected with —what looks like— a rock floating above. In ball and chain, something similar is happening: a hunk of concrete with rebar sticking out of it appears to be floating and holding up a bag filled with something below.

Underwater photograph

Image courtesy of the artist

One recognizes the objects and begins to form an aesthetic impression. The scene is set up looking quite soft and beautiful. The lighting is exquisite. Then, slowly, one’s sense of visual orientation begins to turn woozy. The rock can’t be floating above in rock pepper. The concrete can’t be holding up the bag in ball and chain. Which way is up? Are things floating or sinking? Is the camera upside down or upright? The scene of the water tank gives us no answer either—there is no sense of depth or spatial distance. The image exists in an underwater vacuum, equivalent to being in the directionless confines of outer space.

In Almanza Pereda’s underwater films, the added components of time and motion only heighten these tensions. In a glass of fruit, for example; vegetables, fruits, glasses, and plates are arranged on either side of a horizontal plane or shelf. One can’t tell if the objects are resting on the shelf or if the plane is a ceiling keeping them from floating up. Adding to the uncertainty is the way that objects underwater don’t behave as they normally would. When the hand places them down, they roll over or just fall down (or maybe they’re floating up). Air bubbles are released from a plate and then it goes shooting off upwards. Nothing is as it seems, but we are kept watching by the beauty and tone of the film.

The slow-motion movement in the video matches the moody music that accompanies it. It feels as equally contemplative as it is an aesthetic work demonstrating the illusion of underwater physics. Then, a sudden movement occurs in the water, and the objects on top (or under) the shelf violently take the shock and get blown out of the frame. Elsewhere, a symphony of floating or falling of objects can be seen occurring in both directions at the same time.

Oil painting, concrete; 63 x 62 x 15 cm.

Other works combining images with objects include an ongoing series of works that pair found oil paintings with concrete. In these works, a cast concrete form has partially encased a classical-looking oil painting on canvas. The work suggests an old thrift store painting that has found its way to the construction site and has become set in stone. Meaning “fear of empty spaces’ the Horror Vacui series contrasts the heavy, permanent quality of the concrete with the anonymity of the found painting. In other examples, such as shown in the 15th Biennial in Istanbul in 2017, Almanza Pereda presented works in the series alongside other oil paintings housed in the collection at the Pera Museum.

Currently, Almanza Pereda says he is developing a new film documentary exploring the traditional brick-making processes of Cholula. He is also planning new underwater footage to be taken in a volcanic lake near Nayarit. The brick project, supported by funding from the Black Cube Artist Fellowship, investigates pre-Columbian influences that remain in modern processes still being used in cities today like Puebla. Many of the traditional brick forms of ancient pyramids can be seen contrasting the giant kilns used to fire bricks for commercial and domestic use.

His next underwater project is planned for shooting in a crater near Nayarit. A skiff made of scaffolding and plastic drums will allow him and a crew to work in this volcanic lake whose depth reaches below 300 feet. Looking at pictures of its beautiful scenery, one can only imagine what result Almanza Pereda will come up with.

All images copyright the Artist

Alejandro Almanza Pereda was born in 1977 in Mexico City and has lived and worked in different parts of Mexico and the United States. He has a Master’s degree in Arts from Hunter College, New York, and has held solo shows in institutions like San Francisco Art Institute; Museo El Eco, Mexico City; Art in General New York; Stanley Rubin Center, El Paso TX; and College of Wooster Art Museum Ohio. His work has been featured at the Istambul Biennal, ASU Museum; Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City; Dublin Contemporary 2011, 6a Bienal de Curitiba Brazil, El Museo del Barrio and the Queens Museum in New York. Alejandro has attended the Skowhegan and Bemis Art Residencies program as well as a grant recipient of CIFO Grant Program, the Harpo Foundation, Sistema Nacional de Creadores in México, Harker Award for Interdisciplinary Studies at SFAI, Theodore Randall International Chair in Art and Design at Alfred University and the Black Cube Artist Fellowship. His work was featured in Art 21 close up series. He is currently a member of LA RUBIA TE BESA an Art band project. He currently lives in Guadalajara Mexico.