photo by Joy DeNardo

courtesy Soloway Gallery

Fawn Krieger: The Civics of Metaphysics

In her first solo show in 2010 at Soloway Gallery, New York-based artist Fawn Krieger presented several utilitarian-scale objects made of clay that resembled artifacts. The show’s title —Ruin Value— refers to a concept originating with Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s reveries on the ”state of nature.” The idea was then borrowed by Albert Speer, (Adolph Hitler’s architect) who developed the theory that mimicking the ruins of classical antiquity would leave behind aesthetically pleasing ruins via his architecture. He used this approach for planning the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, where it was hoped that his “pre-ruined” architecture would glorify the German national public image. It was a ready-made historicizing for modern-day society.

The concept of ruin-value presents an important entry point into Krieger’s work. First, one could talk about the materiality of the ruin itself: the physical manipulation of a malleable medium revealing evidence of function or entropy. Next, is how the ruin evokes a sense of both the temporal and eternal—through the allusion of its archeology and permanence. Finally, there is the active role the public monument plays in communicating within a social context.

Through an overview of Krieger’s work, each of these concerns becomes apparent. In it, she gathers ideas of materiality, civics, and the illimitable; presenting them as sculpture, drawing, or performance. Using metaphysical language, one could say her work touches upon physicality, the existential, and the eternal within a wholly integrated spectrum. This isn’t conveyed through some dry, didactic lesson of philosophy though—quite the contrary—one is led to their discovery through her work involving use of the imagination and a playful exploration of “being in the world”. Arriving at the convergence of the immediate and infinite, Krieger’s work appears made by someone attempting to understand how the universe works through its materials, its social interactions, and their metaphysical implications.

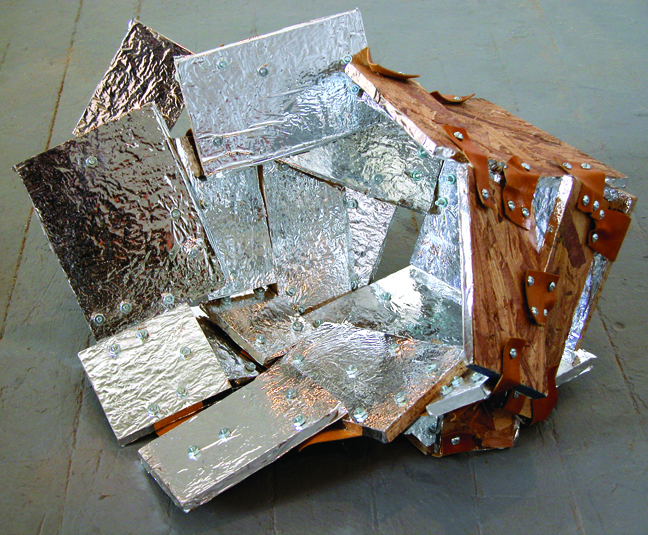

One can begin an approach of these metaphysical implications by looking to Krieger’s use of tactile, malleable mediums. Since the mid-2000s, her work has involved a hands-on, ad-hoc approach to disparate materials. There is also a kind of soft-brutalist vernacular usually present, with primary forms, blocks, and trapezoidal volumes being used. From a body of work titled PASSAGE, for example, the works Dam and Reservoir give an immediate impression of what her material and formal stakes are. Wood, felt, mylar, or leather are slammed together, threaded, and bolted in a way that could be described as being both purposeful and random at the same time.

wood, mylar, felt, thread

20 x 16.5 x 9 inches

wood, mylar, leather, hardware

17.5 x 21 x 11 inches

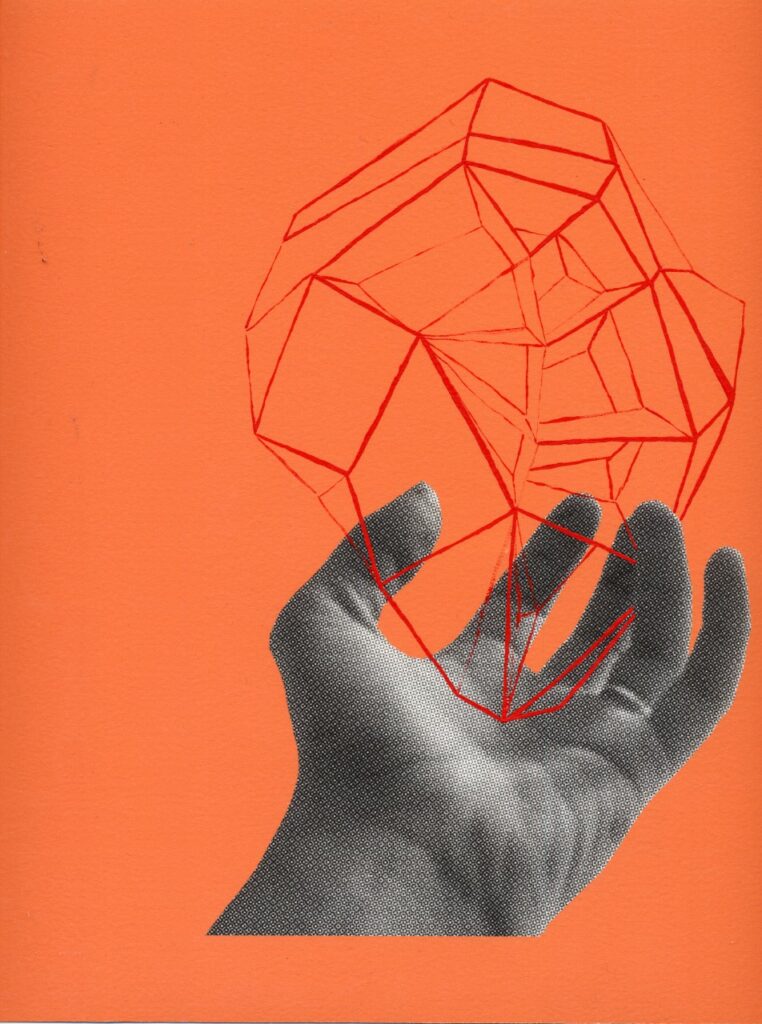

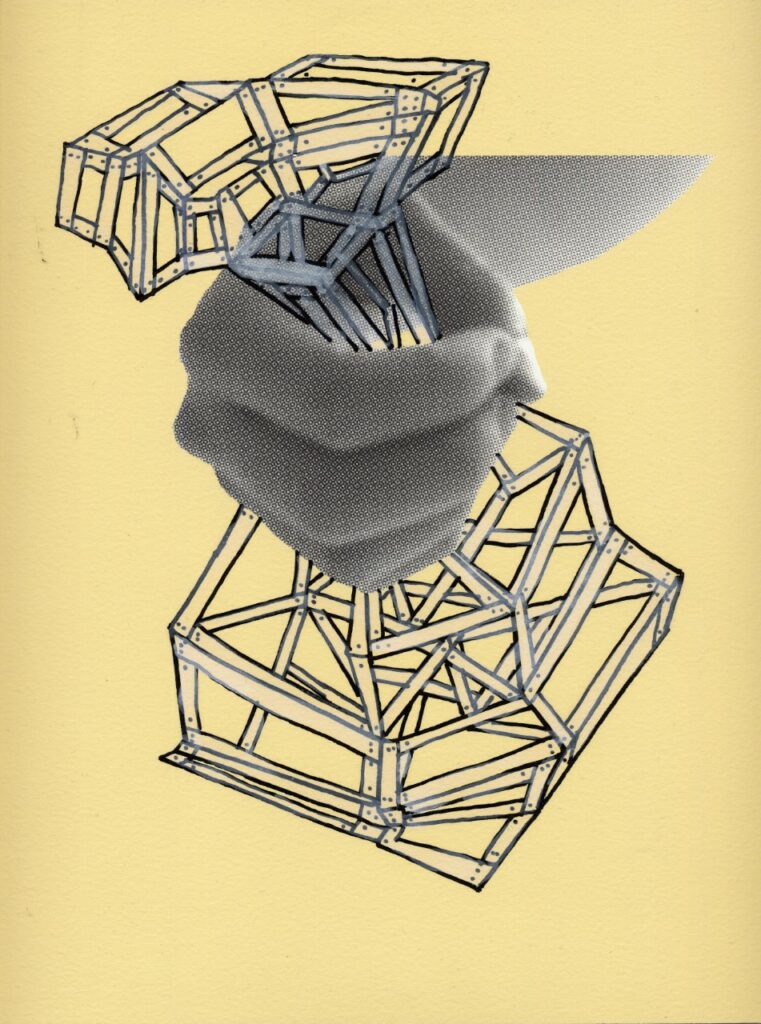

There is a sense of care that goes into these boxy forms approximating the shapes of vessels as well. Krieger’s method of construction seems to be nurturing these budding, primary forms further along their way to becoming actualized. In other works from PASSAGE, she brings the same caring, ad-hoc sensibility to drawing and collage. In these pieces, she draws abstract constructions paired with photography. Similar in form to the material sculptures, the imaginary sculptures here appear in the hand. But instead of approximating other objects like the physical sculptures, these objects remain something to be grasped—like theoretical ideas she is trying to make more real by imagining herself holding them.

Acrylic paint on inkjet print

9.75 x 11.75 in

In her own words, the works from PASSAGE show that “human intervention stands between two natures—the nature of our surroundings and the nature of our intuition.” It could be said of this that one nature is physical and the other is mental. A relationship between the tactile and the theoretical is defined. Both are important in framing our understanding of form and function and how one constructs both concepts and objects.

9.75 x 11.75 in

Acrylic paint on inkjet print

In Ruin Value, Krieger brought this approach to clay. For being an impressionable medium, clay seems a natural choice for her utilitarian, artifactual objects. The material carries connotations of being both historic and kinesthetic at the same time. Besides the concept of ruin value, these works were inspired by the pedagogical methods of Maria Montessori. Montessori’s philosophy was that sensory exploration, culture, language, and physical manipulatives are necessary for one’s development. Like the works from PASSAGE, her ceramic forms in Ruin Value convey physical, psychological, and theoretical qualities.

The objects’ openings and shapes in Ruin Value suggest function and use, while their size suggests handling or manipulation. The implied interaction between the viewer and the objects alludes to performance. From these clues, one understands how Krieger’s sense of materiality is meant to lead us to something else—to an experience or an understanding.

at Soloway Gallery

courtesy Soloway Gallery

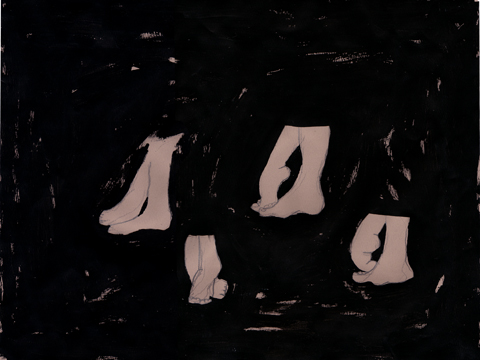

Further into this direction of performance, Krieger refers to her sculptures as “object theaters”. With this read, one begins to view her work as concretized actions, or events that have become physically embodied. The series, titled Haptics, conveys this directly. These drawings capture the “language of touch” by recording bodily positions at different moments in her studio: standing, relaxing, in-action, or observing. The isolated body parts correspond to gestures and forms of the body frozen in their performance— temporal, yet immortalized in gesso and pencil on paper.

black gesso, pencil on paper

10 x 8 inches each

An ongoing project titled First Hand sees Krieger bringing materiality and performance to another level. The project explores sites in Germany called Trümmerberge—artificial mountains built from demolished buildings in the wake of WWII. A primarily female manual labor force was used to build these mountains, presenting an important history of these “rubble women”. In turn, the project also describes a vital artistic model: women, who, in the wake of civic and social destruction took the country’s refuse and created new landscapes for future generations. One of the sites has since become an open-air church, another a gay cruising site, one has an observatory on top, and another is the site where the Munich Massacre of 1972 happened. Krieger’s photographs and objects —made in response to these histories—investigate these women-built landscapes and include her own findings from several of her trips there to study them.

2. First Hand: Drachenberg (R) & Teufelsberg (L), Berlin (2007)

3. First Hand: Olympia Park, Munich (2012)

Other research similarly informs Krieger’s work. In our conversation for this article, she spoke about a trip to explore prehistoric drawings and carvings in Upper Paleolithic caves in Spain. One cave in particular, the Hornos de la Peña cave in the Cantabrian mountains, drew her attention because of an ancient shaman carved on its wall. She described her experience inside this tiny cave with her partner and their guide, turning around to see this magical human figure carved into the wall up close by flashlight. We then talked about the purpose of cave drawings: for communal purposes, for sharing images, or for ritual. The activity of sharing images deep within the earth seems to describe a collective veneration and cognizing of relevant visual forms. It’s not difficult to view Krieger’s work operating the same way.

State of Matter at Soloway Gallery

photo by Joy DeNardo

courtesy Soloway Gallery

Ancient artifacts, brutalism, modern design, and the subject of 20th-century war frame Krieger’s current show—recently opened at Soloway—titled State of Matter. Curated by Soloway’s Founding Co-Director, Annette Wehrhahn, the show consists of some nearly 60 works in the same manageable, interactive scale as in Ruin Value. Most of the works begin with vessel-type forms in clay that have been filled with dyed concrete. Smaller ceramic objects are then pushed into the hardening concrete, squishing out and displacing it. The work describes voids and volumes, resistance and action, material and experience. Here, the physical, the temporal, and the eternal coalesce into a singularity.

The circumstantial evidence surrounding Krieger’s social and metaphysical approach appears in a compendium for the show. The publication is available as both a booklet and pdf and includes images of Krieger’s works photographed in both human-made and natural environments. The publication, with text collected and written by Jenny Nichols (a co-director of Soloway), is analogous to Krieger’s practice —a collection of ideas, quotes, and pictures interacting with the thought processes behind the making of her work. The printed medium performs the same way her objects, performances, and drawings do: sharing understanding through the assembling of materials and ideas.

photo by Joy DeNardo

courtesy Soloway Gallery

In the gallery setting, the explorative levity of Krieger’s objects compliments the collective gravity of materiality, public discourse, haptics, and metaphysics. Color, shape, density, and the objects’ manipulation are communicated through properties, shapes, and relationships forged between actions and things. Krieger’s theatricalizing of the receptivity and resistance of both volume and mass are preserved as physical semiotics. It seems that the universe in all its profundity, and at its most existential, can be demonstrated and explored at this accessible and personal scale.

The frozen, interactive arena reflected in each object shows phenomena scaling from the personal to the universal. They reflect decisions in relation to the innate ways materials behave and act—the nature of our surroundings and our intuition. Rather than the subjects of Krieger’s research being the models we once thought, we realize it’s the other way around—her work is a model that helps us understand everything else.

(All images © Fawn Krieger unless otherwise noted)

-Ian Pedigo

Fawn Krieger is a NY-based artist, whose multi-genre works examine themes of touch, ownership and exchange. Her Flintstonian tactility and penchant for scale compressions reveal an unlikely collision of private and public, where intimate moments also serve as social ruptures. She received her BFA from Parsons School of Design, and her MFA from Bard College’s Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts. Her work has been exhibited at The Kitchen, Art in General, Nice & Fit Gallery, The Moore Space, Von Lintel Gallery, the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University, Portland Institute for Contemporary Art, Human Resources, Fleisher Ollman Gallery, Real Art Ways, Soloway Gallery, and Neon>fdv. Her work has been written about in the New York Times, Artforum, Art in America, Sculpture Magazine, The Brooklyn Rail, NY Arts, Flash Art, and Texte zur Kunst. Krieger is a 2019 Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award Fellow, and has received additional grants from Art Matters Foundation, The Jerome Foundation, and The John Anson Kittredge Educational Fund, She serves as Program Director at The Keith Haring Foundation, Consultant for the Berlin-based MFA & PhD program Transart Institute (part of Else Foundation), and Adjunct Faculty at Adelphi University and Watkins College of Art, now part of Belmont University. Krieger has upcoming residencies at the new Kai Art Center, in Tallinn, Estonia, as well as the Josef & Anni Albers Foundation.